The War on Drugs

The War on Drugs

Crimes are against the state, People (state) v John Doe, indicating the status of crime. The “victim” of a crime is always the state, determining if a wrong against the state has been committed. The libertarian view of victimless crime is a misunderstanding of American jurisprudence, as the state is the only victim in a criminal proceeding. But the sentiment is clear, if the act does no harm to others, in a personal context, it should be deemed harmless to the state. But that is not true.

A wrong against the state can be the aggregate effect of personal acts, which on their own seem harmless, but are determined to be harmful. The war on drugs is exemplary, where individual use is an act deemed harmful individually and in the aggregate. The concept of agregate freedoms constituting state crimes is similar commerce clause usage where congress can regulate intrastate farmers because of the agregate effect on interstate commerce.

The contest is between individual freedoms and state determination of aggregate harm. Libertarian principles of freedoms as long as you do no harm does not address the agregate harm as libertarian views center in individual freedoms.

A libertarian view that agregate harm of personal drug use, a matter of individual freedoms, does no harm, so there is no crime, may be a difficult position in a general election.

—

“I walk down Market Street late at night probably 5 nights a week.

It's a fucking disaster. It's zombie town. It's a morass of human misery, suffering, and crime.

San Francisco has been killing the homeless en masse with permissive empathy, making their lives comfortable on the streets, churning huge amounts of money between overfull city coffees and the NGO-industrial complex. Its a grift machine with a cost measured in dead bodies on the street and ruined lives.

Enough is enough. Just admit that SF has failed to effectively govern itself with regards to crime and homelessness, and call for help. "It's an insult to the SFPD!" - you know what's an insult? Getting a district attorney that doesn't punish crime.

The biggest insult of all, however, was when the city was completely cleaned up in a matter of days - for what? The communist Chinese delegation coming to town. Proving once and for all - the problem is totally fixable with a surge in police presence.

It's gone on too far and too long. Put the pride aside and admit SF needs help. It's in your citizens best interests to not get robbed, have their local grocery stores closed because of theft, cars broken into. It's in the homelesses interests to not have access to open air drug markets too, actually.

"But it's Donald Trump and we hate Trump!" - okay, so you're placing your butthurt partisan politics above the law and order of your own city, the safety of your citizens, the viability of their local businesses, and the health and sanity of it's most vulnerable population? If the national guard was sent in by a democrat president suddenly it'd be okay?

Just solve the problem because it's a national fucking embarassment, and maybe cops here in SF might like some backup. You had every opportunity to fix it and didn't. Time to grow up.”

—

Drugs are not a victimless crime, individually lives are destroyed wholesale and communities are devastated in blight and ruin. The use of drugs causes societal harm.

Weed is not a drug, it’s an herb.

No personal criminal liability for individual use. It’s a state social issue not a federal issue.

Drug smuggling and distribution have catastrophic effects, systemic perpetual degradation of individuals and communities. The solution will be found in NATO, the North American Treaty Organization.

A crime is an act or omission that violates a law and is punishable by the state. For a crime to have been committed, it must include a "guilty act" (actus reus), which is the voluntary action or failure to act that breaks the law, and a "guilty mind" (mens rea), which is the intent to commit the act. The guilty mind and guilty act must generally happen at the same time (concurrence).

Key elements of a crime

Actus reus: The physical or external part of the crime. This can be a positive act, such as hitting someone, or an omission, such as failing to act when there is a legal duty to do so.

Mens rea: The mental or internal part of the crime. It refers to the defendant's state of mind or intent at the time of the act.

Concurrence: The requirement that the guilty act (actus reus) and the guilty mind (mens rea) must occur at the same time.

Harm: The act must cause harm to a community, society, or the state, making it a "public wrong".

Note that crimes are not defined by victimization. “If there is no victim there is no crime”, is non-sequitur. Crime is defined by harm to society not to an individual or “victim”. Arguing before the voting public that drugs smuggling and distribution causes no harm (100,000 dead on fentanyl) is a voting booth loser.

Instead, selective decriminalization is preferred, for example weed. Scope of and penalties for crimes defined by criminal laws can be challenged for overly broad and excessively punitive, but not because there was no victim, no societal harm.

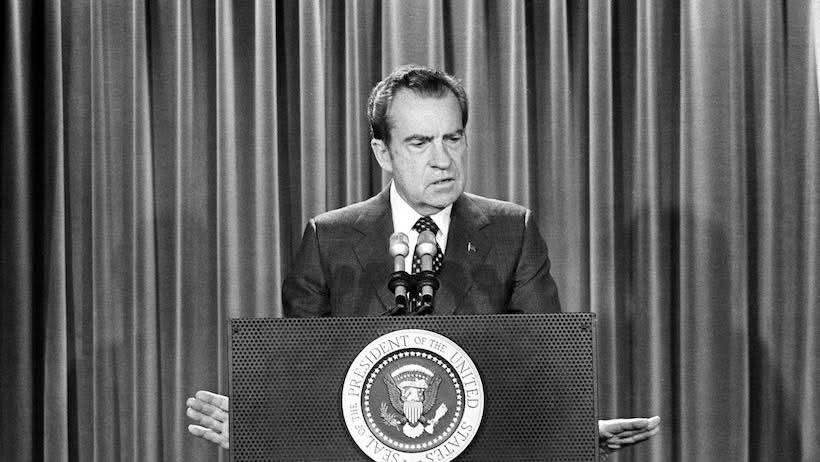

The "War on Drugs" is a global anti-drug campaign led by the U.S. government that began in 1971 under President Richard Nixon. The decades-long initiative has focused on drug prohibition, law enforcement, and harsh penalties to reduce the illegal drug trade and substance use. Critics widely view the policy as a failure that has caused mass incarceration, disproportionately harmed minority communities, and cost over $1 trillion with little effect on drug availability.

History

Early drug laws: Prior to the "War on Drugs" of the 1970s, the U.S. began enacting federal drug legislation in the early 20th century. Early laws, such as the 1909 Smoking Opium Exclusion Act, often targeted marginalized communities like Chinese immigrants.

1971: Nixon's declaration: President Nixon formally declared drug abuse "public enemy number one," a term that was quickly popularized by the media. His administration increased the size and funding of federal drug control agencies, established mandatory minimum sentences, and created the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973.

1980s: "Just Say No": Under President Ronald Reagan, the "War on Drugs" intensified. Mandatory minimum sentences were greatly expanded by the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which allocated billions to law enforcement. First Lady Nancy Reagan also spearheaded the "Just Say No" anti-drug campaign.

Sentencing disparities: The 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act created a stark sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, with possession of five grams of crack triggering a mandatory five-year sentence compared to 500 grams of powder cocaine. Because crack use was prevalent in low-income, predominantly Black communities, this disparity amplified racial bias in the justice system.

Consequences and criticisms

Racial disparities: The Drug Policy Alliance and other critics contend that the "War on Drugs" was intentionally fabricated to disrupt minority communities and anti-war activists. Black and Hispanic individuals are arrested for drug offenses at much higher rates than white people, despite similar rates of drug use.

Mass incarceration: The number of people incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses skyrocketed from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 by 1997. This has led to the U.S. having the highest incarceration rate in the world and has destabilized families and communities.

Negative health outcomes: Rather than functioning as a public health initiative, the punitive focus of the "War on Drugs" has been linked to increased overdose fatalities. Incarcerating people with substance use disorders can make them more vulnerable to overdose after release.

High cost: The "War on Drugs" has cost the United States an estimated $1 trillion since its start, with billions of dollars spent annually on enforcement and incarceration. This spending has come at the expense of funding for other critical services like education and healthcare.

Limited effectiveness: Drug availability remains high, and the street cost of drugs is low. International efforts have failed to end the illegal drug trade, and military interventions have enabled violent criminal organizations.

Alternatives and modern policy shifts

Decriminalization and harm reduction: A growing number of cities and states are moving away from criminalization toward public health approaches, often referred to as harm reduction. Harm reduction acknowledges that abstinence is not always realistic and aims to reduce the harms associated with drug use through interventions like syringe exchange programs and access to medication-assisted treatment.

Public health focus: Treatment has been shown to be more effective and cost-efficient than incarceration for addressing addiction. Decriminalizing possession and expanding access to health services can treat substance use as a medical issue rather than a crime.

Sentencing reform: The U.S. has seen some rollbacks on mandatory minimum sentencing. In 2010, the Fair Sentencing Act reduced the crack and powder cocaine sentencing disparity, and some states have lowered penalties for certain drug offenses.

Shift in rhetoric: In 2009, the Obama administration officially stopped using the "War on Drugs" terminology, and later initiatives have focused on harm reduction services and investments. Legalization of cannabis in many states further reflects a change in public attitudes.